Below you’ll find the full text of the talk I just gave at the Society for Cinema and Media Studies conference in Chicago, as part of a panel on “Post-Cinematic Affect: Theorizing Digital Movies Now” along with Therese Grisham, Steven Shaviro, and Julia Leyda — all of whom I’d like to thank for their great contributions! As always, comments are more than welcome!

Crazy Cameras, Discorrelated Images, and the Post-Perceptual Mediation of Post-Cinematic Affect

Shane Denson

I’m going to talk about crazy cameras, discorrelated images, and post-perceptual mediation as three interlinked facets of the medial ontology of post-cinematic affect. I’ll connect my observations to empirical and phenomenological developments surrounding contemporary image production and reception, but my primary interest lies in a more basic determination of affect and its mediation today. Following Bergson, affect pertains to a domain of material and “spiritual” existence constituted precisely in a gap between empirically determinate actions and reactions (or, with some modification, between the production and reception of images); affect subsists, furthermore, below the threshold of conscious experience and the intentionalities of phenomenological subjects (including the producers and viewers of media images). It is my contention that the infrastructure of life in our properly post-cinematic era has been subject to radical transformations at this level of molecular or pre-personal affect, and following Steven Shaviro I suggest that something of the nature and the stakes of these transformations can be glimpsed in our contemporary visual media.

My argument revolves around what I’m calling the “crazy cameras” of post-cinematic media, following comments by Therese Grisham in our roundtable discussion in La Furia Umana (alternatively, here): Seeking to account for the changed “function of cameras […] in the post-cinematic episteme,” Therese notes that whereas “in classical and post-classical cinema, the camera is subjective, objective, or functions to align us with a subjectivity which may lie outside the film,” there would seem to be “something altogether different” in recent movies. “For instance, it is established that in [District 9], a digital camera has shot footage broadcast as news reportage. A similar camera ‘appears’ intermittently in the film as a ‘character.’ In the scenes in which it appears, it is patently impossible in the diegesis for anyone to be there to shoot the footage. Yet, we see that camera by means of blood splattered on it, or we become aware of watching the action through a hand-held camera that intrudes suddenly without any rationale either diegetically or aesthetically. Similarly, but differently as well, in Melancholia, we suddenly begin to view the action through a ‘crazy’ hand-held camera, at once something other than just an intrusive exercise in belated Dogme 95 aesthetics and more than any character’s POV […].”

What it is, precisely, that makes these cameras “crazy,” or opaque to rational thought? My answer, in short, is that post-cinematic cameras – by which I mean a range of imaging apparatuses, both physical and virtual – seem not to know their place with respect to the separation of diegetic and nondiegetic planes of reality; these cameras therefore fail to situate viewers in a consistently and coherently designated spectating-position. More generally, they deviate from the perceptual norms established by human embodiment – the baseline physics engine, if you will, at the root of classical continuity principles, which in order to integrate or suture psychical subjectivities into diegetic/narrative constructs had to respect above all the spatial parameters of embodied orientation and locomotion (even if they did so in an abstract, normalizing form distinct from the real diversity of concrete body instantiations). Breaking with these norms results in what I call the discorrelation of post-cinematic images from human perception.

With the idea of discorrelation, I aim to describe an event that first announces itself negatively, as a phenomenological disconnect between viewing subjects and the object-images they view. In her now-classic phenomenology of filmic experience, The Address of the Eye, Vivian Sobchack theorized a correlation – or structural homology – between spectators’ embodied perceptual capacities and those of film’s own apparatic “body,” which engages viewers in a dialogical exploration of perceptual exchange; cinematic expression or communication, accordingly, was seen to be predicated on an analogical basis according to which the subject and object positions of film and viewer are dialectically transposable.

But, according to Sobchack, this basic perceptual correlation is endangered by new, or “postcinematic” media (as she was already calling them in 1992), which disrupt the commutative interchanges of perspective upon which filmic experience depends for its meaningfulness. With the tools Sobchack borrows from philosopher of technology Don Ihde, we can make a first approach to the “crazy” quality of post-cinematic cameras and the discorrelation of their images.

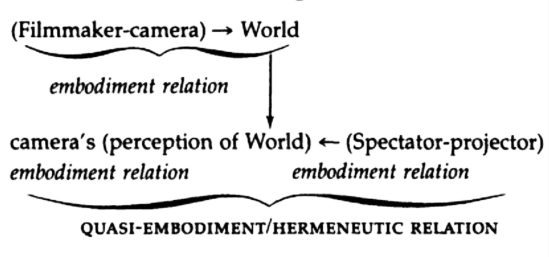

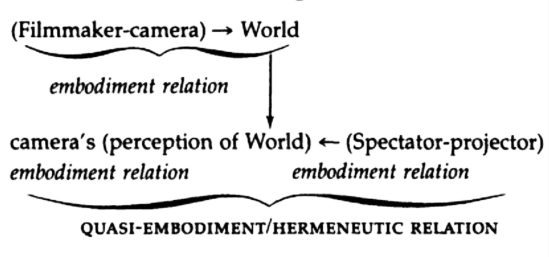

Take the example of the digitally simulated lens flare, featured ostentatiously in recent superhero films like Green Lantern or the Ghost Rider sequel directed by Neveldine and Taylor, who brag that their use of it breaks all the rules of what you can and can’t do in 3D. Beyond the stylistically questionable matter of this excess, a phenomenological analysis reveals significant paradoxes at the heart of the CGI lens flare. On the one hand, the lens flare encourages what Ihde calls an “embodiment relation” to the virtual camera: by simulating the material interplay of a lens and a light source, the lens flare emphasizes the plastic reality of “pro-filmic” CGI objects; the virtual camera itself is to this extent grafted onto the subjective pole of the intentional relation, “embodied” in a sort of phenomenological symbiosis that channels perception towards the objects of our visual attention. On the other hand, however, the lens flare draws attention to itself and highlights the images’ artificiality by emulating (and foregrounding the emulation of) the material presence of a camera. To this extent, the camera is rendered quasi-objective, and it instantiates what Ihde calls a “hermeneutic relation”: we look at the camera rather than just through it, and we interpret it as a sign or token of “realisticness.” The paradox here, which consists in the realism-constituting and -problematizing undecidability of the virtual camera’s relation to the diegesis – where the “reality” of this realism is conceived as thoroughly mediated, the product of a simulated physical camera rather than defined as the hallmark of embodied perceptual immediacy – points to a more basic problem: namely, to a transformation of mediation itself in the post-cinematic era. That is, the undecidable place of the mediating apparatus, the camera’s apparently simultaneous occupation of both subjective and objective positions within the noetic relation that it enables between viewers and the film, is symptomatic of a more general destabilization of phenomenological subject- and object-positions in relation to the expanded affective realm of post-cinematic mediation. Computational, ergodic, and processual in nature, media in this mode operate on a level that is categorically beyond the purview of perception, perspective, or intentionality. Phenomenological analysis can therefore provide only a negative determination “from the outside”: it can help us to identify moments of dysfunction or disconnection, but it can offer no positive characterization of the “molecular” changes occasioning them. Thus, for example, CGI and digital cameras do not just sever the ties of indexicality that characterized analogue cinematography (an epistemological or phenomenological claim); they also render images themselves fundamentally processual, thus displacing the film-as-object-of-perception and uprooting the spectator-as-perceiving-subject – in effect, enveloping both in an epistemologically indeterminate but materially quite real and concrete field of affective relation. Mediation, I suggest, can no longer be situated neatly between the poles of subject and object, as it swells with processual affectivity to engulf both.

Compare, in this connection, film critic Jim Emerson’s statement in response to the debates over so-called “chaos cinema”: “It seems to me that these movies are attempting a kind of shortcut to the viewer’s autonomic nervous system, providing direct stimulus to generate excitement rather than simulate any comprehensible experience. In that sense, they’re more like drugs that (ostensibly) trigger the release of adrenaline or dopamine while bypassing the middleman, that part of the brain that interprets real or imagined situations and then generates appropriate emotional/physiological responses to them. The reason they don’t work for many of us is because, in reality, they give us nothing to respond to – just a blur of incomprehensible images and sounds, without spatial context or allowing for emotional investment.” Now, I want to distance myself from what appears to be a blanket disapproval of such stimulation, but I quote Emerson’s statement here because I think it neatly identifies the link between a direct affective appeal and the essentially post-phenomenological dissolution of perceptual objects. Taken seriously, though, this link marks the crux of a transformation in the ontology of media, the point of passage from cinematic to post-cinematic media. Whereas the former operate on the “molar” scale of perceptual intentionality, the latter operate on the “molecular” scale of sub-perceptual and pre-personal embodiment, potentially transforming the material basis of subjectivity in a way that’s unaccountable for in traditional phenomenological terms. But how do we account for this transformative power of post-cinematic media, short of simply reducing it (as it would appear Emerson tends to do) to a narrowly positivistic conception of physiological impact? It is helpful here to turn to Maurizio Lazzarato’s reflections on the affective dimension of video and to Mark Hansen’s expansions of these ideas with respect to computational and what he calls “atmospheric” media.

According to Lazzarato, the video camera captures time itself, the splitting of time at every instant, hence opening the gap between perception and action where affect (in Bergson’s metaphysics) resides. Because it no longer merely traces objects mechanically and fixes them as discrete photographic entities, but instead generates its images directly out of the flux of sub-perceptual matter, which it processes on the fly in the space of a microtemporal duration, the video camera marks a revolutionary transformation in the technical organization of time. The mediating technology itself becomes an active locus of molecular change: a Bergsonian body qua center of indetermination, a gap of affectivity between passive receptivity and its passage into action. The camera imitates the process by which our own pre-personal bodies synthesize the passage from molecular to molar, replicating the very process by which signal patterns are selected from the flux and made to coalesce into determinate images that can be incorporated into an emergent subjectivity. This dilation of affect, which characterizes not only video but also computational processes like the rendering of digital images (which is always done on the fly), marks the basic condition of the post-cinematic camera, the positive underside of what presents itself externally as a discorrelating incommensurability with respect to molar perception. As Mark Hansen has argued, the microtemporal scale at which computational media operate enables them to modulate the temporal and affective flows of life and to affect us directly at the level of our pre-personal embodiment. In this respect, properly post-cinematic cameras, which include video and digital imaging devices of all sorts, have a direct line to our innermost processes of becoming-in-time, and they are therefore capable of informing the political life of the collective by flowing into the “general intellect” at the heart of immaterial or affective labor.

The Paranormal Activity series makes these claims palpable through its experimentation with various modes and dimensions of post-perceptual, affective mediation. After using hand-held video cameras in PA1 and closed-circuit home-surveillance cameras in PA2, and following a flashback by way of old VHS tapes in PA3, the latest installment intensifies its predecessors’ estrangement of the camera from cinematic and ultimately human perceptual norms by implementing computational imaging processes for its strategic manipulations of spectatorial affect. In particular, PA4 uses laptop- and smartphone-based video chat and the Xbox’s Kinect motion control system to mediate between diegetic and spectatorial shocks and to regulate the corporeal rhythms and intensities of suspenseful contraction and release that define the temporal/affective quality of the movie. Especially the Kinect technology, itself a crazy binocular camera that emits a matrix of infrared dots to map bodies and spaces and integrate them algorithmically into computational/ergodic game spaces, marks the discorrelation of computational from human perception: the dot matrix, which is featured extensively in the film, is invisible to the human eye; the effect is only made possible through a video camera’s night vision mode – part of the post-perceptual sensibility of the video camera that distinguishes it from the cinema camera. The film (and the series more generally) is thus a perfect illustration for the affective impact and bypassing of cognitive (and narrative) interest through video and computational imaging devices. In an interview, (co)director Henry Joost says the use of the Kinect, inspired by a YouTube video demonstrating the effect, was a logical choice for the series, commenting: “I think it’s very ‘Paranormal Activity’ because it’s like, there’s this stuff going on in the house that you can’t see.” Indeed, the effect highlights all the computational and video-sensory activity going on around us all the time, completely discorrelated from human perception, but very much involved in the temporal and affective vicissitudes of our daily lives through the many cameras and screens surrounding us and involved in every aspect of the progressively indistinct realms of our work and play. Ultimately, PA4 points toward the uncanny qualities of contemporary media, which following Mark Hansen have ceased to be contained in discrete apparatic packages and have become diffusely “atmospheric.”

This goes in particular for the post-cinematic camera, which has shed the perceptually commensurate “body” that ensured communication on Sobchack’s model and which, beyond video, is no longer even required to have a material lens. This does not mean the camera has become somehow immaterial, but today the conception of the camera should perhaps be expanded: consider how all processes of digital image rendering, whether in digital film production or simply in computer-based playback, are involved in the same on-the-fly molecular processes through which the video camera can be seen to trace the affective synthesis of images from flux. Unhinged from traditional conceptions and instantiations, post-cinematic cameras are defined precisely by the confusion or indistinction of recording, rendering, and screening devices or instances. In this respect, the “smart TV” becomes the exemplary post-cinematic camera (an uncanny domestic “room” composed of smooth, computational space): it executes microtemporal processes ranging from compression/decompression, artifact suppression, resolution upscaling, aspect-ratio transformation, motion-smoothing image interpolation, and on-the-fly 2D to 3D conversion. Marking a further expansion of the video camera’s artificial affect-gap, the smart TV and the computational processes of image modulation that it performs bring the perceptual and actional capacities of cinema – its receptive camera and projective screening apparatuses – back together in a post-cinematic counterpart to the early Cinématographe, equipped now with an affective density that uncannily parallels our own. We don’t usually think of our screens as cameras, but that’s precisely what smart TVs and computational display devices in fact are: each screening of a (digital or digitized) “film” becomes in fact a re-filming of it, as the smart TV generates millions of original images, more than the original film itself – images unanticipated by the filmmaker and not contained in the source material. To “render” the film computationally is in fact to offer an original rendition of it, never before performed, and hence to re-produce the film through a decidedly post-cinematic camera. This production of unanticipated and unanticipatable images renders such devices strangely vibrant, uncanny – very much in the sense exploited by Paranormal Activity. The dilation of affect, which introduces a temporal gap of hesitation or delay between perception (or recording) and action (or playback), amounts to a modeling or enactment of the indetermination of bodily affect through which time is generated, and by which (in Bergson’s system) life is defined. A negative view sees only the severing of the images’ indexical relations to world, hence turning all digital image production and screening into animation, not categorically different from the virtual lens flares discussed earlier. But in the end, the ubiquity of “animation” that is introduced through digital rendering processes should perhaps be taken literally, as the artificial creation of (something like) life, itself equivalent with the gap of affectivity, or the production of duration through the delay of causal-mechanical stimulus-response circuits; the interruption of photographic indexicality through digital processing is thus the introduction of duration = affect = life. Discorrelated images, in this respect, are autonomous, quasi-living images in Bergson’s sense, having transcended the mechanicity that previously kept them subservient to human perception. Like the unmotivated cameras of D9 and Melancholia, post-cinematic cameras generally have become “something altogether different,” as Therese put it: apparently crazy, because discorrelated from the molar perspectives of phenomenal subjects and objects, cameras now mediate post-perceptual flows and confront us everywhere with their own affective indeterminacy.