Lately, there has been a lot going on around here in the area of TV studies: the Film & TV Reading Group recently discussed Jason Mittell’s work, and we are preparing to discuss that of Lynn Spigel; moreover, these two scholars, Mittell and Spigel, will be giving keynotes at the “Cultural Distinctions Remediated” conference, which is being co-organized by the Initiative for Interdisciplinary Media Research. Also, Jason Mittell is giving a series of workshops in Göttingen, in association with the DFG Research Unit “Popular Seriality — Aesthetics and Practice.” And in Hannover, Florian Groß has been teaching a seminar on Mad Men, while a number of interesting student projects are currently dealing with a variety of contemporary television series. In this context, and against the background of discussions of “Quality TV,” “narrative complexity,” and, more generally, of narrative TV, I’d like to point to some alternative avenues that I’ve been exploring — avenues that, while in no way opposed to the type of work that’s been going on of late, might enrich TV studies through a very different set of emphases, objects, and approaches.

The background for this post is that I have just received final confirmation that a paper of mine, “Faith in Technology: Televangelism and the Mediation of Immediate Experience,” has been accepted and will be appearing soon in Phenomenology & Practice. The paper, which attempts a “techno-phenomenology” of faith-healing televangelism and the call to “touch the screen,” has its origins in a collaborative effort between myself and Christoph Bestian, formerly a sociology grad student here in Hannover. Together, we sought to synthesize our areas of expertise in, respectively, phenomenological approaches to media and the sociology of religion in order to forge a type of media analysis that would be more robust than either of the individual approaches in isolation — a polyvocal approach able to draw strength from interdisciplinary dialogue and differences of perspective. Of course, I take full responsibility for any shortcomings in this product of our collaboration, but I am grateful to Christoph for challenging my views and placing them alongside a very different tradition of inquiry. What I’d like to suggest is that perhaps a similarly productive encounter is possible between the phenomenological perspective that I outline in the paper on televangelism and the topics and approaches of TV studies; especially studies that emphasize the self-reflexivity of contemporary television stand to profit, I believe, from a detailed phenomenological analysis of embodied reception — not as a replacement for, but as a complement to, the more standard narratological perspectives.

In any case, this is work that remains to be done. My paper on televangelism does not engage directly with work in the field of TV studies, but it might be seen as laying a foundation for that sort of encounter. Here is the abstract for the paper:

This paper seeks to illuminate the experiential structures implied in the viewing of televangelistic programming — with particular focus on programming of the charismatic faith-healing variety that culminates in the televangelist’s appeal to viewers to “touch the screen” and consummate a communion that transcends the separation implied by the televisual medium. By way of a “techno-phenomenological” analysis of this marginal media scenario, faith-healing televangelism is shown to involve experiential paradoxes that are tied to processes of social marginalization as well. Thus, it is argued, faith-healing televangelism functions as a call to viewers to mount a head-on confrontation with the technological infrastructure of secular modernity and thereby to effect a specifically material negotiation of evangelical culture’s precarious balancing act between an entrenchment in and a self-marginalization from the secular mainstream.

*************

And here is the original introduction to the paper, which has now fallen to the cutting-room floor, but which gives an idea of the paper’s approach and the scope of the argument:

*************

Faith in Technology: Televangelism and the Mediation of Immediate Experience

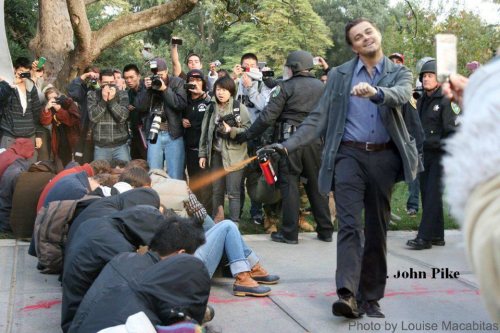

Shane Denson

What is it like to watch televangelism? For many late-night channel surfers, televangelism occasionally provides a form of entertaining diversion unsurpassed on the fringe-media landscape of infomercials and call-in astrology consultations for its ability to render parody superfluous. If, however, the spectacles of mass-mediated religion offer amusement to the unbeliever, they can as readily generate an unsettling experience of disbelief: how can anyone, such a viewer may ask, take these transparent displays of charlatanry seriously? Watching televangelism as unintentional comedy is therefore a short-lived entertainment, for its pleasures are both predicated upon and potentially undermined by a distanced attitude, one that implies a critical difference from, and thus also a particular reading of, what it must be like for true believers to watch the shows. Thus, entertainment easily gives way to a form of armchair sociology or media psychology, and the humor of a televangelist asking us to put our hand on the screen to feel the power of the holy spirit becomes diluted by a concern for, or a disdain of, the “other” viewer: one naïve enough to buy into the promises of spiritual fulfillment and worldly prosperity that are peddled like so much snake oil. Like the promised rewards, the investments being solicited are both spiritual and material, and the spectacular lifestyle enjoyed by some televangelists, flying in private jets from one engagement to the next to spread the gospel to an audience that includes some of the poorest members of society, attests both to the existence of the true believer and to the dishonorable motivations of many TV preachers. Indeed, perennial sex and fraud scandals have made it common knowledge that televangelists don’t always practice what they preach, thus making it hard for our late-night ironic viewers to sympathize with their exploited counterparts.

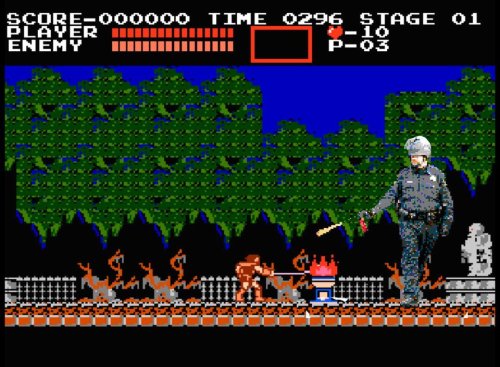

Interpreting televangelists’ praxeological inconsistencies not just as typically human failures but as straightforward hypocrisy, the increasingly cynical viewer may detect broader contradictions in the televangelistic enterprise. The conservative theology espoused on the airwaves often seems quite at odds with the modern secular world, and yet televangelism is inextricably tied up with modernity. TV ministries often engage directly in worldly politics, lending their support to causes ranging from anti-pornography crusades to the waging of mechanized wars on foreign soil. Even more centrally, religious conservatives never tire of condemning “the media,” not just for the perceived liberal slant or indecency that characterizes mainstream media contents but also for the isolating effects of modern technological forms of mediation; paradoxically, though, televangelism is dependent for its very existence on precisely these technologies of mass communication.

However, focusing on these apparent contradictions fails to capture some of the most significant paradoxes of televangelism. Certainly, part of the reason is that the perspective outlined above — that of “the cynic” — is based on simplifying stereotypes of televangelists, their modes of address, and their audiences. Not only is there a wide range of theological content represented in today’s religious programming, but also a variety of styles and formats employed in televangelism (religious talk shows, alternative news programs, infomercial-type paid programming, issue-based fundraisers, preacher-centered motivational shows, and televised congregational church services, among others). Accordingly, it is impossible to identify a singular implied viewer or a coherent audience base of televangelism. The supposed contradictions with which televangelism is charged, it might be argued, are partially generated by lumping these differences indiscriminately together. Nevertheless, the cynic’s view does touch upon one of the central issues that any analysis of televangelism must confront—the tension between conservative evangelical theology and the mediating technology of television. But we fail to appreciate the tension’s true import so long as we reduce it to a competition between an anti-modern message and a modern channel of dissemination. At stake is not a message per se at all, I suggest, but an experience that is seen as immediate — the direct communion of the holy spirit with a believer’s body and soul. The question, then, is this: how can an inherently immediate experience be communicated through electronic media?

Posing the question in this way requires that we go beyond the dichotomies of form/content or channel/message and focus instead on the embodied experience of viewing televangelism. Recognizing the variety of televangelism’s forms and modes of address, I seek not to reify one monolithic type of televangelistic experience but to address a paradigm case in which the tension between mediation and immediatism reaches its apex: the case of the televangelist faith-healer’s appeal to viewers to touch the screen and consummate a laying on of hands at a distance. As a preliminary step towards such a phenomenological analysis, we must contextualize televangelism historically and socially and reconsider the relations between conservative evangelicalism and modern processes of secularization. As I shall demonstrate, there is an inherent connection between the two that is obfuscated by emphasizing evangelicalism’s overt rejections of secular modernity. At the level of religious practice, conservative evangelicalism and fundamentalism are less anti-modern movements than they are attempts to provide an alternative experience of modernity. As one field of such practice, televangelism is a decidedly modern phenomenon; it aims not to disseminate a pre-existing (and pre-modern) message but actively produces new constellations of discursive content and experience that are intrinsically tied to modernity and its technologies. Seen from this angle, the televangelist’s invitation to touch the TV screen is an invitation to confront modernity head on, to undergo not just a test of faith but to submit oneself to a technological ordeal in which a qualitatively new form of faith may emerge that is tuned to and inseparable from the technological conditions of modernity. Thus, rather than writing off viewers’ interaction with the screen as simple-minded naiveté that overlooks a damning contradiction, we must come to appreciate the dynamic, productive potential of the experiential paradox.