Full text of the talk I presented at the SCMS conference today:

Post-Cinematic Affect, Collectivity, and Environmental Agency

Shane Denson (Duke University)

The computational and broadly post-cinematic media at the heart of contemporary moving images are involved in a massive transformation of human agents’ phenomenological relations to the world. Digital imagery has long been held accountable for effacing the indexicality of cinema’s photographic base, while post-cinematic images more generally might be thought in terms of what I call their “discorrelation” from viewing subjects. However, there is a flip-side to these negative determinations that I want to highlight: if the microtemporal and subperceptual operations of post-cinematic media bypass and hence displace subjective perception, they also serve to expand the material domain and efficacy of sub- and supra-personal affect. What this amounts to, ultimately, is a radical empowerment of the nonhuman environment, the agency of which becomes tangible in sites and forms ranging from the Fitbit to “big data” and the computational modeling of climate change.

In this presentation, which is divided into three sections, I want to take this thought a step further. I want to show, ultimately, that new forms of collectivity may become thinkable and, hopefully, actionable in the spaces opened up by post-cinematic media.

Part 1: Irrational Cameras. Let me start by summarizing an argument I have made elsewhere about the transformation of the camera and its images in a post-cinematic media regime. Post-cinematic cameras – by which I mean a range of imaging apparatuses, both physical and virtual – seem not to know their place with respect to the separation of diegetic and nondiegetic planes of reality; these cameras therefore fail to situate viewers in a consistently and coherently designated spectating-position.

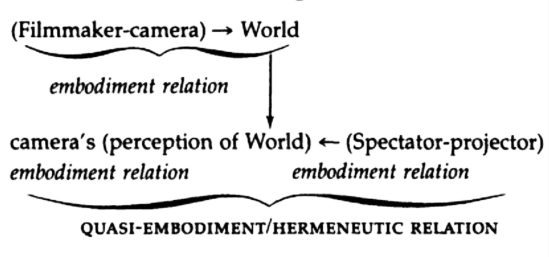

Take the example of the digitally simulated lens flare, which a phenomenological analysis reveals to be riddled with perceptual paradoxes. On the one hand, the CGI lens flare encourages what philosopher of technology Don Ihde calls an “embodiment relation” to the virtual camera: by simulating the material interplay of a lens and a light source, the lens flare emphasizes the plastic reality of “pro-filmic” CGI objects; the virtual camera itself is to this extent grafted onto the subjective pole of the intentional relation, “embodied” in a sort of phenomenological symbiosis that channels perception towards the objects of our visual attention. On the other hand, however, the lens flare draws attention to itself and highlights the images’ artificiality by emulating (and foregrounding the emulation of) the material presence of a camera. To this extent, the camera is rendered quasi-objective, and it instantiates what Ihde calls a “hermeneutic relation”: we look at the camera rather than just through it, and we interpret it as a sign or token of “realisticness.”

The paradox here, which consists in the realism-constituting and realism-problematizing undecidability of the virtual camera’s relation to the diegesis – where the “reality” of this realism is conceived as thoroughly mediated, the product of a simulated physical camera rather than defined as the hallmark of embodied perceptual immediacy – points to a more basic transformation of mediation itself in the post-cinematic era. That is, the undecidable place of the mediating apparatus, the camera’s apparently simultaneous occupation of both subjective and objective positions within the noetic relation that it enables between viewers and the film, is symptomatic of a more general destabilization of phenomenological subject- and object-positions in relation to the expanded affective realm of post-cinematic mediation. Computational, ergodic, and processual in nature, media in this mode operate on a level that is categorically beyond the purview of perception, perspective, or intentionality. Phenomenological analysis can therefore provide only a negative determination “from the outside”: it can help us to identify moments of dysfunction or disconnection, but it can offer no positive characterization of the “molecular” changes occasioning them. Thus, for example, CGI and digital cameras do not just sever the ties of indexicality that characterized analogue cinematography (an epistemological or phenomenological claim); they also render images themselves fundamentally processual, thus displacing the film-as-object-of-perception and uprooting the spectator-as-perceiving-subject – in effect, enveloping both in an epistemologically indeterminate but materially quite real and concrete field of affective relation. Mediation, I suggest, can no longer be situated neatly between the poles of subject and object, as it swells with processual affectivity to engulf both.

Part 2: The dilation of affect. What I have been describing here is a decentering of human perception and an empowerment of the larger environment. In order to account for this transformation, it will be helpful here to invoke Mark Hansen’s notion of “atmospheric media,” a concept that Hansen develops to explain the experiential impact of computation, but which builds upon Maurizio Lazzarato’s theorization of an affective dimension of video technologies.

According to Lazzarato, the video camera captures time itself, the splitting of time at every instant, hence opening the gap between perception and action where affect resides (in the metaphysics of Henri Bergson). Because it no longer merely traces objects mechanically and fixes them as discrete photographic entities, but instead generates its images directly out of the flux of sub-perceptual matter, which it processes on the fly in the space of a microtemporal duration, the video camera marks a revolutionary transformation in the technical organization of time. The mediating technology itself becomes an active locus of molecular change: a Bergsonian body qua center of indetermination, a gap of affectivity between passive receptivity and its passage into action. The camera imitates the process by which our own pre-personal bodies synthesize the passage from molecular to molar, replicating the very process by which signal patterns are selected from the flux and made to coalesce into determinate images that can be incorporated into an emergent subjectivity.

This dilation of affect, which characterizes not only video but also computational processes like the rendering of digital images (which is always done on the fly), marks the basic condition of the post-cinematic camera, the positive underside of what presents itself externally as a discorrelating incommensurability with respect to molar perception. As Mark Hansen has argued, the microtemporal scale at which computational media operate enables them to modulate the temporal and affective flows of life and to affect us directly at the level of our pre-personal embodiment. In this respect, properly post-cinematic cameras, which include video and digital imaging devices of all sorts, have a direct line to our innermost processes of becoming-in-time, and they are therefore capable of informing the political life of the collective by flowing into the “general intellect” at the heart of immaterial or affective labor. Again, this is because the individual’s capacity to perceive is decentered, discorrelated from the perceptual object, and offloaded onto an environment of diffusely “atmospheric” media – including the many screens and cameras, but also the invisible networks and data streams, that surround us everywhere.

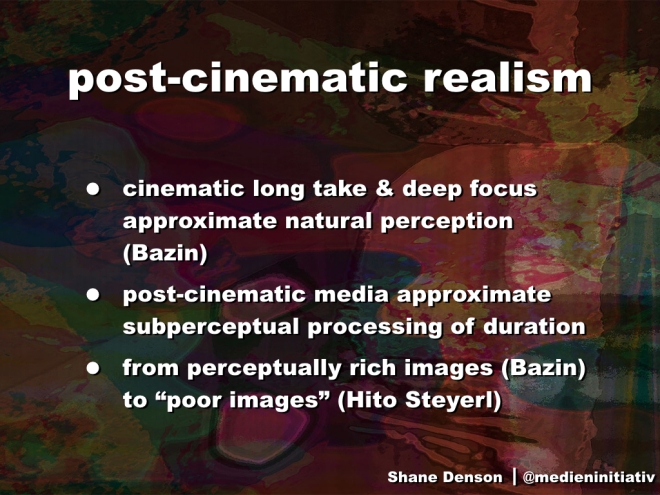

Part 3: Post-Cinematic Realism. Paradoxically, these arguments suggest that post-cinematic media – precisely those media widely credited with destroying the index and thus evacuating the political promise of realism – might in fact be credited with a newly intensified political relevance through their institution of a new, post-cinematic realism.

Whereas Bazin privileged techniques like the long take and deep focus for their power to approximate our natural perception of time and space, Lazzarato and Hansen emphasize post-cinematic media’s ability to approximate the sub-perceptual processing of duration executed by our pre-personal bodies. The perceptual discorrelation of images gives way, in other words, to a more precise calibration of machinic and embodied temporalities; simultaneously, the perceptual richness of Bazin’s images becomes less important, while “poor images” (in Hito Steyerl’s term) communicate more directly the material and political realities of a post-cinematic environment.

Consider the 2015 horror flick Unfriended, which is presented as the screen recording of one of the characters’ laptops. Reflecting what Francesco Casetti calls the “relocation” of cinema from the big screen to a variety of little ones, the movie’s sense of “realism” is especially heightened when you watch it on your own laptop. We witness everything on this single screen, through Skype conversations, Facebook chats, email, and web browsing. And it’s essential for the movie that it’s presented in “real-time.” This adds to the temporal urgency and speaks to the reality of our own online communications today, thereby establishing a sense of realism despite the fantastic/supernatural elements at play, and articulating this reality despite—or precisely through—the use of digital glitches. These might otherwise be taken to signal the interruption of realism by the intercession of digital processing that breaks the indexical continuity between image input and image output, but such glitches are a familiar reality of online communication (on platforms like Skype), and our involvement in the images is increased by their use; for example, we might wonder whether the glitches are diegetic, or whether they are produced on our own machine during playback, either due to the buffering processes of online streaming platforms, or because we downloaded a faulty torrent file from some dubious website. Realism here is constructed through an immediacy and direct exploration of the new media-technical conditions of life, to which we can all more or less relate. But in the process the glitches also expose the movie’s singular screen as, in fact, double: the site of playback, traditionally a passive “screening” surface, the screen is also revealed as a newly active site or space in which images are processed and generated before our very eyes. The glitches point up the perceptual paradoxes of post-cinematic cameras, as I’ve described them with respect to CGI lens flares, but they additionally implicate the post-cinematic screen, which becomes ontologically indistinguishable from the camera in its execution of the same material processes of microtemporal and subperceptual image generation.

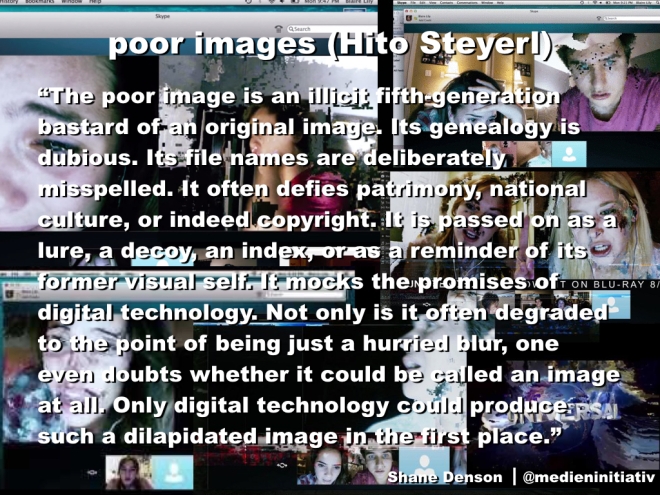

These glitches, and their relation to our contemporary media-technical realities, call attention to what Hito Steyerl has called the “poor images” that circulate in digital networks. Following Steyerl, these images provide an important context for thinking about the political realities of moving-image media today—and an important context for thinking about post-cinematic realism more generally. In Steyerl’s words: “The poor image is an illicit fifth-generation bastard of an original image. Its genealogy is dubious. Its file names are deliberately misspelled. It often defies patrimony, national culture, or indeed copyright. It is passed on as a lure, a decoy, an index, or as a reminder of its former visual self. It mocks the promises of digital technology. Not only is it often degraded to the point of being just a hurried blur, one even doubts whether it could be called an image at all. Only digital technology could produce such a dilapidated image in the first place.” These poor images are close in spirit to the “imperfect cinema” called for in the name of Third Cinema movements, in that they register social marginalization processes while also creating publics of their own. But they also outline the dark side of a “participatory culture,” whose democratic promise is compromised by the hierarchies of value that remain and by the exploitation of unpaid fan labor that is enlisted in the ongoing production-consumption circuits of networked images. Without extracting themselves from these conflicting political trajectories, according to Steyerl, poor images might nevertheless—or precisely for this reason—create what Dziga Vertov called “visual bonds” capable of subverting official and mainstream valuations by expressing what Steyerl terms a “link to the present.” In this way, degraded, glitched-out images might fulfill the political promise of realism precisely through their material connection to the post-indexical infrastructures of moving-image media. In Steyerl’s words: “The poor image is no longer about the real thing—the originary original. Instead, it is about its own real conditions of existence: about swarm circulation, digital dispersion, fractured and flexible temporalities. It is about defiance and appropriation just as it is about conformism and exploitation. In short: it is about reality.”

Like Steyerl, Lazzarato also refers to Vertov and his idea of the “visual bond,” which is seen as a materialist alternative to the critique of ideology, the expression of a practice that addresses the ontology of media directly and prior to the level of content. Essentially, by resisting reduction to human perception, the images of Vertov’s kino-eye are discorrelated from molar experience but thereby opened to the molecular processes by which duration is processed both biologically and technologically, thus getting to the heart of the process by which subjectivities and social collectives are produced. If Bazin described a cinematic realism that draws for its political power on an approximation to perceptual experience, then Vertov marks the path towards a post-cinematic realism that takes aim at the process by which the subject of that perceptual experience takes shape in the first place. It does this, according to Lazzarato, by means of the pre-personal affect that is marshaled and modulated by the increasingly fine-grained “time-crystallizing machines” of cinema, video, and digital processors. Accordingly, the video art of Nam June Paik is seen as a Vertovian answer to television, not because it counters the ideological content of TV but because it probes the machinic time itself of the apparatus, freeing it from the exclusive control of state and corporate interests. The latter, according to Lazzarato, contribute to the production and regulation of political subjects through their control of technical standards (like the PAL and NTSC standards that regulate image frequency, color spectrum, and aspect ratio); because the power to modulate the speeds and images dictated by such standards is “withdrawn from social praxis” (78), our affective powers are impoverished, and we are left with what Lazzarato calls a “‘poor’ perception” (78). The ontology of time-crystallizing machines thus gives way to an ethics or politics of the standards, codes, or protocols upon which images or perceptual objects are formed and synchronized with emergent subjects and social collectives. And because they expose the materiality of digital file formats, video codecs, and compression algorithms, today’s poor images harbor a significant political promise, a potential for resistance that can be deployed creatively against the impoverishment and standardization of perception.

It is debatable, finally, whether a movie like Unfriended actually succeeds in this respect. Certainly, at the level of its narrative, it apparently fails to articulate anything like a model of social-political resistance; if anything, its teenage drama of betrayal, suicide, and revenge, all mediated by the networks and interfaces of social media, and leading to the death of the entire group of “friends,” serves as a critique of contemporary socialization processes – an ideological critique that takes aim not only at online bullying, for example, but that exposes an infrastructure of communication and of intersubjective relation that has rendered the term “friend” itself highly unstable in the age of Facebook. But beyond this more overt political critique of today’s highly mediated forms of collectivity, the movie’s use of glitches serves to focus attention, and to channel affect, at a deeper level, where subjectivity itself is being produced and modulated in an environment of microtemporally operating machines and protocols. Glitches serve at times like micro-cliffhangers, causing us to wait for the image to buffer or clear up so that we can see what’s going on. In this respect, the movie simulates the familiar and yet always disconcerting experience of network lag, e.g. in our own Skype conversations, when the temporal continuity of protentional-retentional experience is interrupted, giving rise to a feeling like that of a cartoon character who has gone over the edge of a cliff, but remains suspended, floating momentarily between the certainty of solid ground and a realization of the situation’s gravity. These micro-cliffhangers focus our attention on the material infrastructure of experience itself, causing us to see pixels as the components but also as material obstacles to vision, blocky screen objects that, despite ourselves, we try to look around to see what’s on the other side. And in this space of the screen, seemingly unitary but, as we have seen, doubled and in fact multiplied even further by the machinic and social networks in which it participates (both diegetically and materially), our vision is dispersed, divided. We are forced to scan the screen for relevant information; our gaze is not sutured, not directed, and to this extent we are hailed not as an integral subject, but as a bundle of affects engaged in a collective effort to perceive—an effort that is both enabled and hindered by the protocols and agencies of the media environment, out of which our subjectivities are wrought. Unfriended may or may not ultimately facilitate our efforts to take control of this experiential infrastructure, but perhaps it succeeds in gesturing towards the fact that this effort must be a collective one, aimed at constructing collectivity in the first place, and that it must be mounted around and in relation to the affective technologies of our post-cinematic environment.