[vimeo 80345330 w=500&h=280]

Pioneering video artist Nam June Paik has been quoted as saying that video “imitates not nature but time.” Somewhat more elaborately, in his reflections on “input-time” and “output-time,” he writes: “Video art imitates nature, not in its appearance or mass, but in its intimate ‘time-structure’ … which is the process of AGING (a certain kind of irreversibility).” And elsewhere again, Paik explains his view thus: “So called ‘feedback’, video artist’s favorite word, is nothing but the scientific term for ‘aging’ … that is : enrichment in time-component or a compounded time. Like any other art, video-art also imitates the nature… but in her time-component. Ex. : in NTSC color, color is determined by time-component : that is : phase-delayline in 3.58 mega-hertz.”

Paik’s views on video’s novel relation to temporality inspired philosopher Maurizio Lazzarato to take up the question of time’s modulation in the machines of post-Fordist capitalism in his book Videofilosofia: La percezione del tempo nel post-fordisme (the first chapter of which has appeared in English in Theory, Culture & Society). And Lazzarato’s reflections (along with those of Steven Shaviro and Mark B. N. Hansen, among others) have been central to my own attempts to come to terms with the significance and experiential parameters of our shift to a properly “post-cinematic” media regime.

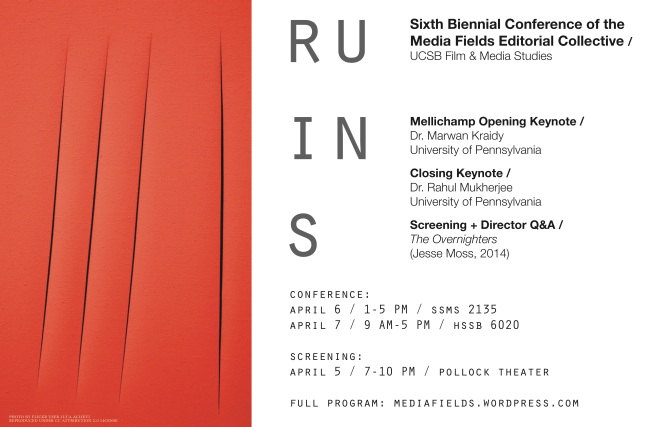

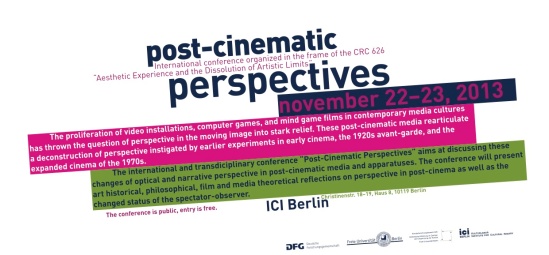

This past weekend (November 22-23, 2013), I had the opportunity to present my work on the topic at the excellent “Post-Cinematic Perspectives” conference organized by Lisa Åkervall and Chris Tedjasukmana from the Freie Universität Berlin. Steven Shaviro’s talk on Spring Breakers was a particular highlight for me, but I also enjoyed being exposed to thoughts on a number of topics and artworks quite outside my areas of expertise — especially a number of talks on very recent video-art pieces with which I was not previously familiar but am now inspired to seek out.

Through some serendipitous cosmic event — some alignment of the stars giving rise to an unhoped-for coincidence of spatiotemporal coordinates, intellectual and practical concerns, and the respective times of work and leisure — I also found myself confronted with Nam June Paik’s wonderful Triangle: Video-Buddha and Video-Thinker (1976/1991), currently on display in the exhibit “Body Pressure: Sculpture since the 1960s” at Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart (25 May 2013 – 12 January 2014). Placing a sculpture of Buddha and a small reproduction of Rodin’s Le Penseur under the constant, real-time surveillance of two video cameras connected to four monitors — two of which face each other in a closed-circuit loop of video production and machinic reception — Paik’s Triangle provided the perfect opportunity not only to think more about the “metabolic images” that (following Paik, Lazzarato, Shaviro, and Hansen) I had been theorizing at the conference, but to put these thoughts into practice in an experimental configuration.

[vimeo 80345329 w=500&h=280]

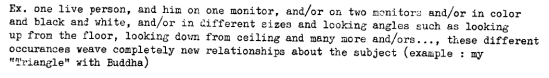

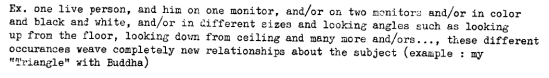

Of course, the fact that (following the advent of the smartphone) virtually everyone today walks around with a high-definition digital video camera in their pocket has no small bearing on the significance and historicity of Paik’s work. Thus, my wife and I decided to expand Triangle‘s loop of time-metabolizing images by adding a further layer of video processing: each of us filmed different points of the sculpture’s own input/output and integrated our own video devices into the loop. The results, seen here, were synced and combined with split-screen and transparency settings (along with reverse-motion in the top video and the introduction of compression artifacts in the bottom one). In this way, we tried to expand and reflect (materially, not cognitively) on the impact of computational imaging technologies for a work like Triangle — on their radical expansion of variables (“and/ors”) which Paik described thus:

In the talk I gave over the weekend, “Nonhuman Perspectives and Discorrelated Images in Post-Cinema” (abstract here), I argued (drawing on Lazzarato’s very Paikian arguments about video):

Computational rendering processes generate unanticipated and unanticipatable images, in effect rendering post-cinematic cameras themselves strangely vibrant, uncanny. There is a dilation of affect involved, which introduces a temporal gap of hesitation or delay between perception (or recording) and action (or playback), and it amounts to a modeling or enactment of the indetermination of bodily affect through which time is generated, and by which (in Bergson’s system) life is defined. A negative view sees only the severing of the images’ indexical relations to world, hence turning all digital image production and screening into animation. But in the end, the ubiquity of “animation” that is introduced through digital rendering processes should perhaps be taken literally, as the artificial creation of (something like) life, itself equivalent with the gap of affectivity, or the production of duration through the delay of causal-mechanical stimulus-response circuits; the interruption of photographic indexicality through digital processing is thus the introduction of duration = affect = life. Discorrelated images, in this respect, are autonomous, quasi-living images in Bergson’s sense, having transcended and gained a degree of autonomy from the mechanicity that previously kept them subservient to human perception. Apparently “crazy,” because discorrelated from the molar perspectives of phenomenal subjects and objects, cameras now mediate post-perceptual flows and confront us everywhere with their own affective indeterminacy.

Another way to put this is to say that post-cinematic cameras and images are metabolic processes or agencies, and their insertion into the environment alters the interactive pathways that define our own material, biological, and ecological forms of being, largely bypassing our cognitive processing to impinge upon us at the level of our own metabolic processing of duration. Metabolism is a process that is neither in my subjective control nor even confined to my body (as object) but which articulates organism and environment together from the perspective of a pre-individuated agency. Metabolism is affect without feeling or emotion – affect as the transformative power of “passion” that, as Brian Massumi reminds us, Spinoza identifies as that unknown power of embodiment that is neither wholly active nor wholly passive. Metabolic processes are the zero degree of transformative agency, at once intimately familiar and terrifyingly alien, conjoining inside/outside, me/not-me, life/death, old/novel, as the basic power of transitionality – marking not only biological processes but also global changes that encompass life and its environment. By insinuating themselves into the molecular flows of affect, prior to the possibility of perception and action, metabolic images have a direct impact on “the way we tick” — i.e. on the material production and modulation of time and temporal experience.

In many ways, the original assemblage of Paik’s Triangle already demonstrated what I call the metabolic work of microtemporal image processing. Today, however, it provides further opportunities for experimentation with the spatial and temporal parameters of our existence in conjunction with the many cameras and screens that connect us with our contemporary environment. Expanding the variables of the work’s “and/or” configurations, our cameras can hook into Paik’s assemblage, enter into its feedback loops, but also transport those loops into larger contexts of metabolic processing and transport. Images circulate within and beyond, effectively confounding distinctions between object and process, thing and environment. By engaging with the work and aiming our cameras at it in this way, we too are hooked into the system, and our own embodied perception is displaced as it is integrated into the molar and molecular configurations that situate and underpin conscious experience. In this way, Paik’s work continues today to probe the technical modulations of time and affective life in the era of convergence, computation, and our properly post-cinematic environment.

[vimeo 80355324 w=500&h=280]