On the occasion of our “Chaos Cinema” film series, where the topic yesterday was Michael Bay’s Transformers (2007), I gave a short talk on the notion of “discorrelated images” — an idea that percolates (though is not named as such) in my dissertation, emerging through conversation with a number of thinkers, ideas, and images: Deleuze (and Guattari) on “affection images” and “faciality,” Henri Bergson on living (and other) “images,” Brian Massumi on affect and “passion,” Mark Hansen on the “digital facial image” and “the medium as environment for life,” and others, including Boris Karloff and the iconic image of Frankenstein’s monster. All of which are left out of the picture in yesterday’s talk — which was designed to set the stage for further thinking, to be suggestive rather than definitive, and thus serves more to raise questions than to answer them. In any case, I reproduce the text (and slides) here, in case anyone is interested:

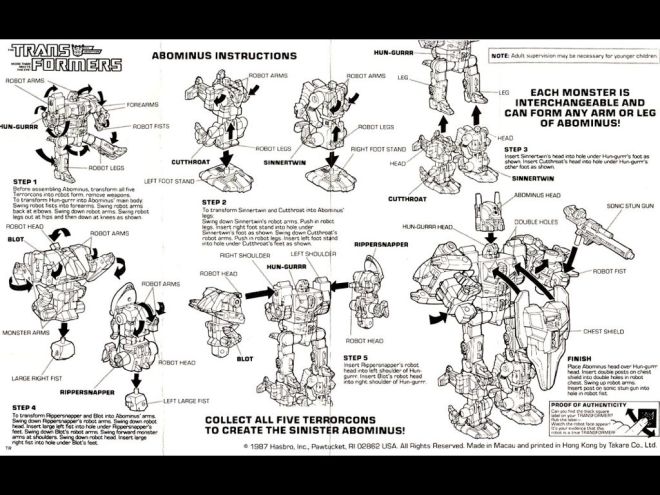

Michael Bay’s 2007 film Transformers can be seen as an interesting case of transmedial serialization in the context of what Henry Jenkins calls our “convergence culture” — interesting because, reversing the typical order of merchandising processes, Bay’s film and its sequels are part of a franchise that originates with (rather than giving rise to) a line of toys. Unlike Star Wars action figures, for example, which are extracted from narrative contexts and made available for supplementary play, Transformers are toys first, and only subsequently (though promptly) narrativized. These toys, first marketed in the US by Hasbro in 1984, but based on older Japanese toylines going by other names, spawned several comic-book series, Saturday-morning cartoons, an animated film, novelizations, video games implemented across a wide range of platforms, and the trilogy of films directed by Michael Bay with backing from Steven Spielberg.

Despite such rampant adaptation and narrativization, however, we shouldn’t lose sight of the toys, which continue to be marketed to kids today, nearly thirty years after they were first marketed to me and my elementary school friends: the toys themselves offer only the barest of narrative parameters (good guys vs. bad guys) for the generation of storified play scenarios. Transformers, in opposition to Star Wars figures, which always exist in some relation to preexistent stories, are not primarily interesting from a narrative point of view at all: Autobots and Decepticons are basically just two teams, and the play they generate need not be any more narratively complex than a soccer or football match (where tales are told, to be sure, but as a supplement to the ground rules and the moves made on their basis).

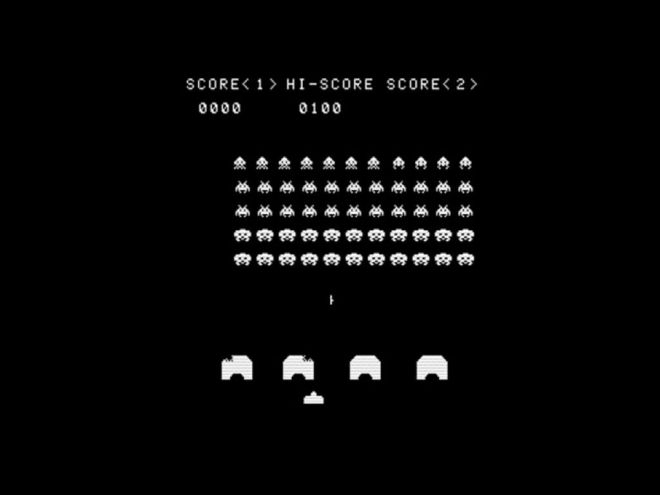

Instead, the basic attraction of Transformers is, as the name says, the operation of transformation. Transformers are therefore mechanisms first, and the attraction for children (mostly boys) growing up in the early 80s was to see how they worked. Transformers, in other words, are the perfect embodiments of an “operational aesthetic” in the original sense of the term, first introduced by Neil Harris to describe the attraction of P.T. Barnum’s showmanship against the background of nineteenth century freak shows, magic shows, World Expos, and popular exhibitions of the latest technologies. More recently, Jason Mittell has usefully employed the concept to explain the attraction of “narratively complex television,” but the operationality at issue here (i.e. in the case of the Transformers) is of a stubbornly non-narrative sort. Thus, consonant with a general trait of science-fiction film (with its narratively gratuitous displays of special effects, which often interrupt the story to show off the state of the art in visualization technologies), narrativizations of Transformers are inherently involved in competitions of interest: story vs. mechanism, diegesis vs. medium. The Transformers themselves, who are more interesting as mechanisms than as characters, are the crux of these alternations.

(On this basis we might say, riffing on Niklas Luhmann, that they embody an “operative difference between substrate and form” and thus themselves constitute the “media” of a flickering cross-medial serial proliferation. But that’s another story…)

Let me go back to the idea of convergence culture, which I’d like to connect with this operational mediality. It’s important to keep in mind that our convergence culture, in Jenkins’s terms, is enabled by a different type of convergence with which it remains in constant communication: viz. the specifically technological convergence of the digital. Is it stretching things to say that the original toys latched onto an early eight-bit era fascination with the way electronic machines could generate interactive play? In other words, they spoke to an interest in the way machines worked — as the basic object of interactive video games — and promoted fantasies of artificial intelligences and robotic agencies that would be a match for any human subject (or gamer).

In any case, Michael Bay’s Transformers, along with the film’s sequels, would not be possible without much more advanced digital technologies; the films know it, we know it, and the films know we know it, so the role of the digital is not hidden but foregrounded and positively flaunted in the films. Typically for a transitional era of media-technological change, which, it would seem, we are still going through with respect to the digitalization of cinema (and of life more broadly), there is a fascination with medial processes that the films hook into. The result is that attentions are split between diegesis and medium, story and spectacle. The Transformers serve as a convenient fulcrum point for such oscillations, thus capitalizing on the uncertain valencies of media change while connecting phenomenological dispersal with a story that in some ways speaks to a larger decentering of human perspectives and agencies in the face of convergence and computation processes — to a feeling of contingency about the human that is related in various ways to digital technologies.

For example, there’s a sense of powerlessness with respect to digitally automated finance, which employs robotically operating algorithms to expedite the process and efficiency of transactions, splitting major operations into distributed micro-scale packet transfers that occur faster than the blink of an eye, and at truly sublime scales — both infinitesimally smaller and faster than human sensory ratios and with the potential to produce cataclysmically large results. The entire realm of human action, which exists in between these scales, is marginal at best: the machines originally meant to serve the interests of (some) humans end up serving only the algorithms of a source code — with respect to which, we are perhaps only bugs in the system. It is easy to extrapolate sci-fi fantasies: for example, the emergence of Skynet — or is it Stuxnet?

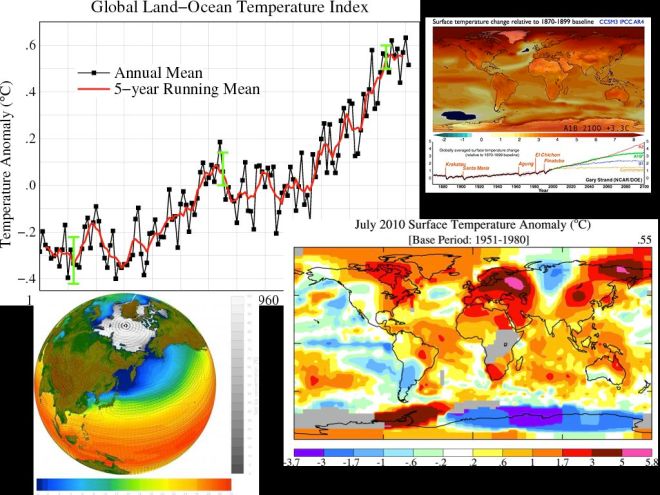

But the decentering of the human perspective through digital technology is taking place in much less fantastic manners, and in ways that do not support any kind of humans-first narratives of heroic reassertion: global warming, which is revealed to us through digital modeling simulations, points not towards our roles as victims of a pernicious technology of automation, but shows us to be the culprits in a crime the scale of which we cannot even begin to imagine. Categorically: we cannot imagine the scale, and this fact challenges us to rethink our notions of morality in ways that would at least attempt to account for all the agencies and ways of being that fall outside of narrowly human sense ratios, discourses, cultural constructions, senses of right and wrong, the true and the beautiful, the false and the ugly…. Through digital technologies, we have found ourselves in an impossible position: our technologies seem to want to live and act without us, and our world itself, ecologically speaking, would apparently be far better off without us. We are forced, in short, to try to think the world without us.

“Without us” can mean both “in our absence” or “beyond us” — outside our specific concerns, attachments, and modes of engagement with the world. The attempt to think, in this sense, “the world without us” characterizes the goal of “speculative realism,” a recent tendency in philosophy defined by its opposition to what Quentin Meillassoux calls “correlationism,” or the idea that reality is exhausted by our means of access to it. Against this notion, which correlates human thought and being on a metaphysical level, the speculative realists challenge us to think the world apart from our narrow view of it, to renounce an essentialism of the human perspective, and to escape to the “Great Outdoors.”

What does this have to do with Transformers and so-called “chaos cinema”? I’m trying to suggest something about the affective state, the structure of feeling, that produces and is (re)produced in and by our media culture today — a structure of feeling that Steven Shaviro calls “post-cinematic affect.” This broader context is largely ignored in Matthias Stork’s conception of “chaos cinema,” which is defined narrowly and technically, in terms of a break with classical continuity. These breaks do occur, and Stork has demonstrated their existence quite powerfully in his video essays, but they are only symptomatic of larger shifts. Shaviro has put forward a seemingly related notion of “post-continuity,” but he is careful to point out that continuity is not what’s centrally at stake. Post-cinematic affect is not served or expressed solely by breaking with principles of continuity editing; rather, continuity is in many instances simply beside the point in relation to a visceral awareness and communication of the affective quality of our historical moment of indeterminacy, contingency, and radical revision. The larger significance of a break with principles of classical continuity editing — rather than just sloppy filmmaking, as Stork sometimes seems to suggest, or quasi avant-garde radicalism — has instead to do with the correlation of continuity principles with the scales and ratios of human perception. Suture and engrossment in classical Hollywood works because those films structure themselves largely in accordance with the ways that a human being sees the world. (It goes without saying that this perceptual model is one that has as its touchstone a normative model of human embodiment, neurotypical cognitive functioning, and relatively unmarked racial, class, and gender types.) And while it has long been clear to feminist critics, among others, that the normative model of (unqualified, unmarked) humanity to which classical film speaks was in need of problematization, I would argue that the human itself has become a problem for us, and that “our” films have registered this in a variety of ways. The momentary breaks with continuity that Stork singles out as the defining features of chaos cinema are just one of the ways.

More generally, I suggest, we witness the rise of the discorrelated image: an image that problematizes, if not altogether escaping, the correlation of human thought and being. The teaser trailer for Transformers (also integrated into the film itself) uses nonhuman subjective shots — images seen through the eyes of a robot, the Mars rover Beagle 2 — to promote its story about an intelligent race of machines. In a somewhat different vein, The Hurt Locker opens with images mediated through the camera-eyes of a robot employed for defusing bombs from a distance. The Paranormal Activity series employs a variety of robotic or automated camera systems. Wall-E, Cars, and a host of other digital animation films are all about the perceptions, feelings, and affects of nonhuman machines. Of course, there’s nothing new about such representations, and they are highly anthropomorphic besides. But what if these are just primers, symptomatic indicators, or gentle nudges, perhaps, towards something else? (Significantly, both Jane Bennett, in the context of her notion of “vibrant matter,” and Ian Bogost, with regard to his project of “alien phenomenology,” have argued for the necessity of a “strategic anthropomorphism” in the service of a nonhuman turn.) In fact, what we find here is that the representational level in such films is coupled with, and points toward, an extra-diegetic fact about the films’ medial mode of existence: digital-era films, heavy with CGI and other computational artifacts, are themselves the products of radically nonhuman machines — machines that, unlike the movie camera, do not even share the common ground of optics with our eyes. Accordingly, the supposed “chaos” of “chaos cinema” is not about a break with continuity; rather, it’s about a break with human perception that materially conditions the cinema (and visual culture more broadly) of the early 21st century. Again, in Transformers, the process of transformation is the crux, the site where discorrelation is most prominently at stake as the object of an operational aesthetic. The spectacle of a Transformer transforming splits our attention between the story and its (digital) execution, between the diegesis and the medial conditions of its staging, which are in turn folded back into the diegesis so as to enhance and distribute a more general feeling of fascination or awe.

What do we see when a Transformer transforms? What we don’t see, necessarily, is a break with the principles of continuity editing. Instead, we witness a discorrelation of the image by other means: we register the way in which our desire to trace the operation of the machine is categorically outstripped by the technology of digital compositing, which animates the transformation by means of algorithmic processes operating on the scale of a micro-temporality that is infinitesimally smaller and faster than any human subject’s ability to process or even imagine it. These images, I contend, are the raison d’etre of the film itself. But they are not “for us,” except in the sense that they challenge us to think our contingency, to intuit or feel that contingency on the basis of our sensory inadequacy to the technical conditions of our environments. A hopeful story, complete with adolescent love interest and other minor concerns, counters this vision of our own obsolescence. But the discorrelated image of transformation is the aesthetic crux of the film, quite possibly the only thing worth watching it for, and perhaps even the bearer of a (probably unintentional) ethical injunction, beyond the rather flimsy human-centered narrative (and the clearly conservative politics, militarism, and apparent misogynism): the discorrelated image, in which the process of transformation can only be suggested to our lagging sensory apparatuses, challenges us performatively, by confronting us with an image of our own discorrelation; viscerally, it asks us to attune ourselves to an environment that is broader than our visual capture of it, faster than our ability to register it, and more or less indifferent to our concernful perception of it. Materially, medially, and ontologically true to the 1980s tagline, the discorrelated images of Michael Bay’s Transformers are indeed “More than meets the eye!”