If the medium is the message, as Marshall McLuhan famously claimed, then the so-called “selfie” may be less about the face that constitutes the recognizable content of such an image, and more about a deeper, less obvious form of material-aesthetic mediation with respect to the transformation of “self” in an age of ubiquitous post-cinematic cameras.

Clearly, such acts of mediation have many levels. On the one hand, we “stage” or “perform” our selves for ourselves and for our friends (and, of course, for our Facebook “friends”); at the same time, though, we do so with an awareness of the machinery of geolocated surveillance and algorithmic facial recognition systems that we feed and help to optimize with the offering of our selfies (and the metadata they contain). Is this a self-destructive tendency or an act of defiance? Do we taunt and shake our fists at the invisible all-seeing God of Hyperinformatic Imagery (or the NSA), heroically though baselessly asserting our autonomy despite our knowledge of its baselessness? Or is it just that we have resigned ourselves to the new “situation,” in which Berkeley’s maxim esse est percipi has been made a reality through a media-technical dispositif that renders superfluous the whole apparatus of angelic and divine perceptions that Bishop Berkeley still needed to keep his system from falling apart?

But the post-cinematic camera is a post-perceptual camera. Esse is now post-percipi in the sense that networks of digital and increasingly “smart” cameras are not just collecting images of “you” or “me” but instituting radical changes in the fine-grained, “molecular” scale of temporal becoming that subtends subjective (or “molar”) perception. As I have been arguing recently (see here, for example), post-cinematic cameras produce “metabolic images” — images that operate outside of visual or perceptual registers and modulate our pre-personal relations to the environment, directly influencing us at the level of our metabolic processing of duration and relation through which our embodied agencies are defined. This has to do with (among other things) the sheer speed of computational processes, which outstrip our own cognitive and perceptual processing abilities. But it also has to do with the affective density that post-cinematic cameras themselves accrue by virtue of the gap — what Bergson would call a “center of indeterminacy,” or simply a body — that these cameras install between the input and output of images, in the space of their microtemporal computational processing. On this basis, a synchronization of human and technical temporalities is made possible at the micro-level. And perhaps this is the hidden message of the medium: the selfie is not just a paradoxical performance of self (in the way that, say, reality shows problematize authenticity), it is in fact the product of a whole new ecology of agency, an ecology of anthropotechnically co-ordinated metabolisms invisibly subtending the visible images by which we seek to represent our “selves.”

With every selfie, we experiment with this interplay of visible manifestation and invisible infrastructure. Who can we be, now, and in relation to an environment filled with rapidly proliferating digital images, where everything is in flux, nothing apparently stable? Perhaps we encounter here, and try to dispel, an old fear in a new guise: that the camera is capable of stealing our souls — both through integration into systems of surveillance, and in the dissolution of our former agencies when set in relation to the molecular, metabolic processes embodied by the post-cinematic camera. In the words of Montreal-based indie rock band Arcade Fire:

What if the camera Really do Take your soul? Oh no... Hit me with your flashbulb eyes! Hit me with your flashbulb eyes! You know I've got nothing to hide You know I got nothing No I got ... nothing

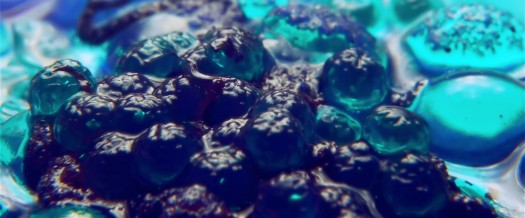

Above, my own mixed-media “reflections” on the problem of the selfie in the age of metabolic modulation. Featuring artworks by Thomas Böing (Ohne Titel [Museum König], 2006), currently on display at the impressive Kolumba — Art Museum of the Archdiocese of Cologne as part of the exhibition “show cover hide. Shrine. An exhibition on the aesthetics of the invisible,” which runs until August 25, 2014.