Over at Figure/Ground Communication, there is a new interview up with Dylan Trigg (whose blog Side Effects you’ll find linked in the sidebar here). The whole interview is well worth your time, but especially interesting (and relevant to the focus of this blog) is the following question and answer:

Is phenomenology still relevant in this age of information and digital interactive media?

Phenomenology is especially relevant in an age of information and digital media. Despite the current post-humanist “turn” in the humanities, we remain for better or worse bodily subjects. This does not mean that we cannot think beyond the body or that the body is unchallenged in phenomenology. Phenomenology does not set a limit on our field of experience, nor is it incompatible with the age of information, less even speculative thinking about non-bodily entities and worlds. Instead, phenomenology reminds us of what we already know, though perhaps unconsciously: that our philosophical voyages begin with and are shaped by our bodily subjectivity.

It’s important to note here that phenomenology’s treatment of the body is varied and complex. It can refer to the physical materiality of the body, to the lived experience of the body, or to enigmatic way in which the body is both personal and anonymous simultaneously. In each case, the body provides the basis for how digital media, information, and post-humanity are experienced in the first place. Phenomenology’s heightened relevance, I’d say, is grounded in the sense that these contemporary artefacts of human life tend to take for granted our bodily constitution.

But phenomenology’s relevance goes beyond its privileging of the body. It has become quite fashionable to critique phenomenology as providing a solely human-centric access to the world. This, I think, is wrong. One of the reasons why I’m passionately committed to phenomenology is because it can reveal to us the fundamentally weird and strange facets of the world that we ordinarily take to be clothed in a familiar and human light. Phenomenology’s gesture of returning to things, of attending to things in their brute facticity, is an extremely powerful move. Merleau-Ponty will speak of a “hostile and alien…resolutely silent Other” lurking within with the non-human appearance of things. For me, the lure of this non-human Other is a motivational force in my own work. It reminds us that no matter how much we affiliate ourselves with the familiar human world, in the act of returning to the things themselves, those same things stand ready to alienate us.

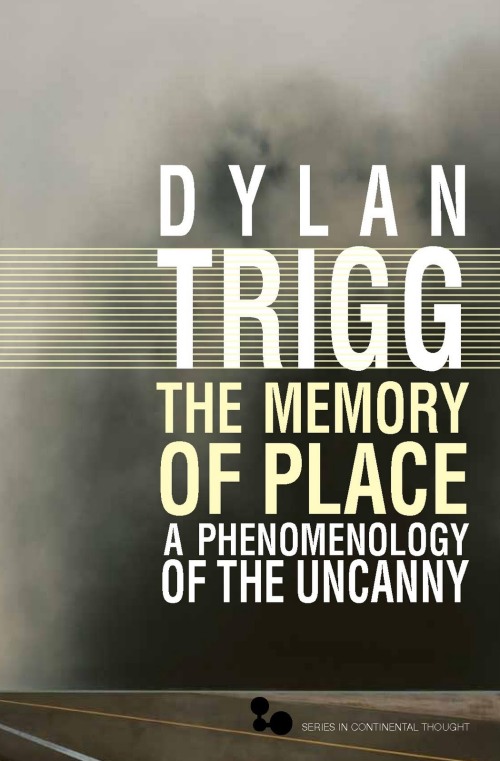

(The image at the top of this post, by the way — and lest there be any confusion about the matter — is not a picture of Dylan Trigg but of body-augmentor extraordinaire, performance artist Stelarc.)