Readers of the blog will recognize this post’s title — “We have never been natural” — as the nutshell slogan for postnaturalism, as it is developed in my forthcoming book of the same title. Now that slogan is also the title of a talk I will be giving at the 2014 Society for European Philosophy and Forum for European Philosophy joint annual conference, “Philosophy After Nature,” which will take place September 3-5, 2014 in Utrecht, Netherlands.

In the talk, I try to get to the media-philosophical heart of postnaturalism and develop the core argument to the extent possible in a 20-minute presentation. Here is the abstract:

We Have Never Been Natural: Towards a Postnatural Philosophy of Media

Shane Denson (Leibniz Universität Hannover / Duke University)

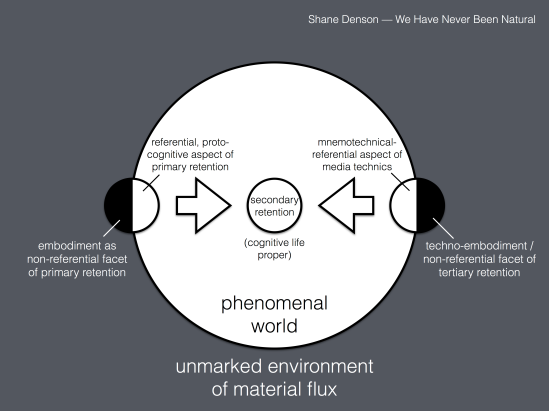

In this presentation, I draw upon concepts and arguments put forward by Bernard Stiegler, Mark B. N. Hansen, Niklas Luhmann, and Bruno Latour and put them into conversation with one another in order to develop what I term a postnatural philosophy of media. Postnaturalism, as I define the term, does not signal the end of nature but a particular manner of rethinking it. Methodologically, postnaturalism marks an extension of rather than a break with (scientific and epistemological) naturalism and its insistence on material evolution as the basis of consciousness and all ideational, symbolic, or discursive realities. Substantively, however, this extension implies a rethinking of nature because technical agencies are seen as not only immanent to the natural but also crucially implicated in the transformative force of evolution. Accordingly, postnaturalism implies that “we have never been natural” (and neither has nature, for that matter). At the heart of this rethinking is what I call the “anthropotechnical interface”: a sub-phenomenal, infra-empirical stratum of materiality, which forms the site of radical transformation by means of the “unnatural selection” that results from the technical mediation of embodied life. This view, which can be developed with the help of Bernard Stiegler’s philosophy of technology, implies a special role for media; accordingly, as I argue, media serve as nothing less than the “originary correlators” of the phenomenal and the noumenal.

My argument for this (seemingly extravagant) claim involves an adaptation of Niklas Luhmann’s systems-theoretical conception of mediality, which (when subjected to a transformative rethinking that abstracts media beyond the system-immanent position to which they are relegated in Luhmann’s thought) provides a formal model for thinking media as the site of sub-phenomenological changes taking place at the very cusp between systemic enclosure and the unmarked environment from which any and all systems emerge. Expanding on Mark B. N. Hansen’s notion of media as the “environment for life” itself, my argument goes on to question the cognitive or mnemotechnical bias of Stiegler’s philosophy of technology while also reversing Hansen’s asymmetrical privileging of human embodiment in the transductive relation between organic and inorganic agencies. Ultimately, the postnatural philosophy of media that results from these encounters works to articulate together process-oriented and object-oriented perspectives; besides (and beyond) empirically determinate manifestations in the form of discrete apparatic entities, media play a wholly non-anthropic role in the production of the empirical, in the constitution and maintenance of its spatio-temporal foundations. As a matter of “distributed embodiment,” media play a literally central role in the transduction of materially intersecting entities, each with their own form of embodiment, their own manner of marking the boundary, embodying the membrane, between material flux and the emergent realm of discrete objects.

Bibliography:

Denson, Shane. Postnaturalism: Frankenstein, Film, and the Anthropotechnical Interface. With a foreword by Mark B. N. Hansen. Bielefeld: Transcript, forthcoming 2014.

Hansen, Mark. Embodying Technesis: Technology Beyond Writing. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 2000.

_____. “Media Theory.” Theory, Culture & Society 23.2-3 (2006): 297-306.

_____. New Philosophy for New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004.

_____. “‘Realtime Synthesis’ and the Différance of the Body: Technocultural Studies in the Wake of Deconstruction.” Culture Machine 6 (2004). <http://www.culturemachine.net/index.php/cm/article/view/9/8>.

Latour, Bruno. We Have Never Been Modern. Trans. Catherine Porter. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1993.

Luhmann, Niklas. Art as a Social System. Trans. Eva M. Knodt. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2000.

_____. Die Gesellschaft der Gesellschaft. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1997.

_____. Social Systems. Trans. John Bednarz, Jr., with Dirk Baecker. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1995.

Stiegler, Bernard. Technics and Time 1: The Fault of Epimetheus. Trans. Richard Beardsworth and George Collins. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1998.

_____. Technics and Time 2: Disorientation. Trans. Stephen Barker. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2009.

_____. Technics and Time 3: Cinematic Time and the Question of Malaise. Trans. Stephen Barker. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2011.