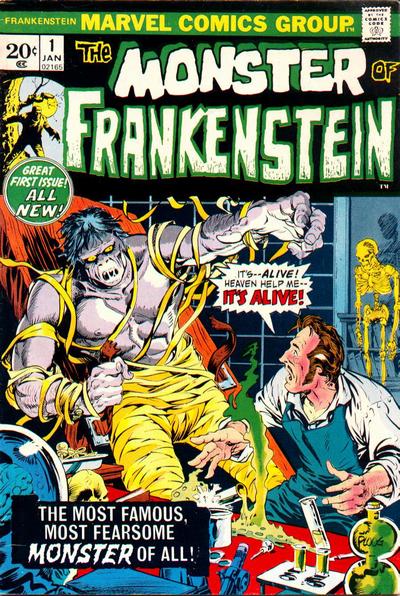

Neulich wurde ich vom Fanzine Zauberspiegel zu meiner Dissertation Postnaturalism: Frankenstein, Film, and the Anthropotechnical Interface und verwandten Themen interviewt. Die Dissertation, deren Cover man hier sieht, wurde von Ruth Mayer (Leibniz Universität Hannover) und Mark Hansen (Duke University) betreut und 2010 bei der Philosophischen Fakultät der Universität Hannover eingereicht. (Während eine überarbeitete Fassung für die Publikation in einem geeigneten Verlag in Vorbereitung ist, ist die als Eigendruck produzierte Dissertation jetzt schon von der Universitätsbibliothek Hannover direkt oder durch den interuniversitären Dissertationentausch erhältlich. (Datensatz bei der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek hier, bei GetInfo hier und im Online-Katalog der Uni Hannover hier.))

Das Interview im Zauberspiegel, das einige allgemein verständliche Antworten auf die in der Dissertation eher technisch und philosophisch behandelte Fragen geben soll, findet man hier: “Shane Denson über Frankenstein, das Monster und ihre Beziehung in Film und Roman.”

Und hier, schliesslich, ist die deutsche Zusammenfassung der Dissertation, die ich der englischsprachigen Arbeit beigelegt habe:

In der vorliegenden Dissertation argumentiere ich, dass filmische Umsetzungen von Mary Shelleys gotischem Roman Frankenstein ein besonderes Licht auf die Historizität von Mensch/Technik-Schnittstellen werfen—zumindest dann, wenn man sich ihnen in einer konsequent historisierenden Weise annähert. Betrachtet man die verschiedenen Filme im Kontext der historischen Zusammenhänge, die zwischen ihren narrativen Inhalten, sozialen Umfeldern und begleitenden kulturellen Konflikten bestehen, setzt man sie in Relation zu medientechnischen Infrastrukturen, Innovationen und Transitionen und verortet man sie genau in den materiellen und lebensweltlichen Parametern des historisch situierten Zuschauererlebnisses—dann lassen die sogenannten Frankenstein-Filme spezifische Konfigurationen der Mensch/Technik-Interaktion erkennen: Muster, Tendenzen und Abweichungen, die die Momente einer von Umbrüchen geprägten Geschichte bilden, die zugleich eine Geschichte des Kinos, der Medien, der Technik und der affektiven Kanäle unserer eigenen Leiblichkeit ist.

Die Arbeit ist in drei Hauptteile gegliedert. Nachdem Kapitel 1 eine Einleitung in die Argumentation und die Begrifflichkeiten der Arbeit liefert, verortet der erste Hauptteil (bestehend aus Kapitel 2 und 3) eine Reihe experienziell-phänomenologischer Herausforderungen, die die Frankenstein-Filme darstellen. Dafür entwickelt Kapitel 2 eine „Technophänomenologie“ der dominanten Film/Zuschauer-Beziehungen unter den Paradigmen des frühen Kinos und des klassischen Hollywood Filmes; diese Perspektive findet dann in der Analyse zweier Frankenstein-Filme aus den jeweiligen filmgeschichtlichen Perioden Anwendung, wobei sich in beiden Fällen eine Destabilisierung zuschauerlicher Relationen zum Film zeigt, die auf einen unbeständigen Zwischenbereich hindeutet, der zwischen den phänomenologischen Regimes des frühen und des klassischen Kinos liegt. In Kapitel 3 verfolge ich diesen Hinweis in die Übergangsperiode des Kinos der 1910er hinein, insbesondere zu dem aus den Thomas-Edison-Studios stammenden Film Frankenstein aus dem Jahre 1910. Wie ich dort argumentiere, deuten die Dualitäten der Adressierung, die in diesem Film exemplifiziert werden, auf eine breiter gefasste Erfahrung der Transitionalität hin, die sich in Bewegung zwischen stabilen Situationen befindet und sich in negativer Weise zur phänomenologischen Subjektivität zeigt—in Form einer unbestimmten Kluft oder Lücke.

Die charakteristische Herausforderung der Frankenstein-Filme verorte ich in diesen Lücken der Transitionalität, und im zweiten Hauptteil der Arbeit versuche ich, ein theoretisches Rahmenwerk—nämlich den „Postnaturalismus“—zu formulieren, das den Provokationen der Filme eine Antwort liefern kann. Kapitel 4 kreist zunächst um die Lücken, die feministische Lesarten von Mary Shelleys Roman an den Tag gelegt haben, bevor ich in diese Lücken eintauche, um dort eine Theorie des prä-personellen und daher nicht diskursiven Kontaktes zwischen menschlichen Körpern und der technischen Materialität zu entdecken. Auf Basis dieses Kontaktes, so mein Argument, sind technische Revolutionen (wie die industrielle Revolution, in deren Gefolge Shelley ihren Roman schrieb) in der Lage, die menschliche Handlungsmacht radikal zu destabilisieren, so dass wir experienzielle Lücken erfahren und textuelle Lücken produzieren—die allerdings rasch aufgefüllt und vergessen werden, wenn wir uns an neue Techniken gewöhnen und sie so „naturalisieren.“ In Kapitel 5 widme ich mich diesen Prozessen im Kontext der Aneignung der Dampfmaschine durch die Thermodynamik, um damit die postnatürliche Historizität der naturwissenschaftlichen Natur selbst aufzudecken—also die Tatsache, die sich nicht auf ein epistemisches Phänomen der diskursiven Konstruktion oder Projektion reduzieren lässt, dass sich die materielle Natur in konstanter Bewegung befindet und dass—aufgrund der Rolle von Techniken in dieser Geschichte—die Natur noch nie „natürlich“ gewesen ist. Kapitel 6 übersetzt diese Ergebnisse in eine postnatürliche Medientheorie, die nicht bloß empirisch individuierte Apparate, sondern auch die Historizität des phänomenologischen Raums betrifft, wie er von menschlichen und nichtmenschlichen Akteuren zusammen artikuliert wird; als filmtheoretisches Korrelat schlage ich eine „kinematische Doppelvision“ vor, die zwischen einer von Merleau-Ponty inspirierten phänomenologischen Sichtweise und einer Bergsonschen Metaphysik pendelt, um die filmische Erfahrung als Produkt eines Wechselspiels zwischen menschlichen Situationen und technischen Verschiebungen zu zeigen.

Der dritte Hauptteil kehrt dann zu den Frankenstein-Filmen zurück, um die besonderen Beziehungen aufzuzeigen, die zwischen ihnen und der postnatürlichen Historizität der anthropotechnischen Schnittstelle bestehen, und eine Art Rapprochement zwischen den konfligierenden menschlichen und nichtmenschlichen Akteuren, die den Filmen innewohnen, zu bewirken. Kapitel 7 folgt diesem Ziel, indem es sich den paradigmatischen Frankenstein-Filmen—James Whales Frankenstein (1931) und Bride of Frankenstein (1935)—widmet und die menschlichen und nichtmenschlichen Perspektiven alternierend aufzeigt, deren Zusammenkunft die zentrale Kreatur der Filme animiert. In dieser Konfrontation—die unentwirrbar im historischen Moment und besonders im Kontext des Übergangs zum Tonfilm eingebettet ist—suche ich eine nicht-reduktive Weise, um die andersartige Kraft zu begreifen, die die durch Frankenstein-Filme provozierten Erfahrungslücken besetzt. Schließlich bietet Kapitel 8 eine synoptische Sichtweise der weiteren Entwicklung der Frankenstein-Filme; hier versuche ich, die aktive Rolle der kinematischen Techniken in der Produktion kurzlebiger Erfahrungen der Transitionalität aufzuzeigen, die unter dem Gewicht unserer habituellen und „natürlichen“ Beziehungen zu jenen Techniken begraben liegen. Das von mir anvisierte Rapprochement besteht also darin, eine Anerkennung der gegenseitigen Artikulation der Erfahrung durch menschliche und nichtmenschliche (technische) Akteure zu fördern, wodurch die affektive und leibliche Erfahrung einer anthropotechnischen Transitionalität nicht arretiert und der menschlichen Dominanz unterjocht wird, sondern experimentell als gemeinsame Produktion unserer postnatürlichen Zukunft angenähert wird. Dies ist die eigentliche Herausforderung der Frankenstein-Filme.