Following Elena del Rio’s post on “Cinema’s Exhaustion and the Vitality of Affect” (to which I responded here), the theme week at in media res on Steven Shaviro’s Post-Cinematic Affect has continued with two great presentations: Paul Bowman’s “Post-Cinematic Effects” and now Adrian Ivakhiv’s “A Hair of the Dog that Bit Us.” Bowman’s presentation is framed by a clip from Old Boy, while Ivakhiv uses Grace Jones’s video “Corporate Cannibal.” Both of these, like del Rio’s presentation on Monday, raise some crucial questions for understanding our contemporary media moment. If you haven’t been following the presentations and discussions, check it out now. Following Patricia MacCormack’s presentation tomorrow, Steven Shaviro is scheduled to respond to all of these takes (and tangents) on his work on Friday.

Tag: Steven Shaviro

Metabolic Images and Post-Cinematic Affect

Over at in media res, the theme week on Steven Shaviro’s Post-Cinematic Affect has gotten underway with an intriguing post by Elena del Rio from the University of Alberta entitled “Cinema’s Exhaustion and the Vitality of Affect,” which I highly recommend reading/viewing. I wanted to post a short response there, but for some reason I am unable to log in to do so. So I’m posting my response here for the time being, but will post again at in media res when possible.

Over at in media res, the theme week on Steven Shaviro’s Post-Cinematic Affect has gotten underway with an intriguing post by Elena del Rio from the University of Alberta entitled “Cinema’s Exhaustion and the Vitality of Affect,” which I highly recommend reading/viewing. I wanted to post a short response there, but for some reason I am unable to log in to do so. So I’m posting my response here for the time being, but will post again at in media res when possible.

(Note that the following draws on ideas that I develop at much greater length in Postnaturalism: Frankenstein, Film, and the Anthropotechnical Interface, which I am currently revising for publication, and attempts to set them in relation to del Rio’s response to Shaviro’s notion of post-cinematic affect.)

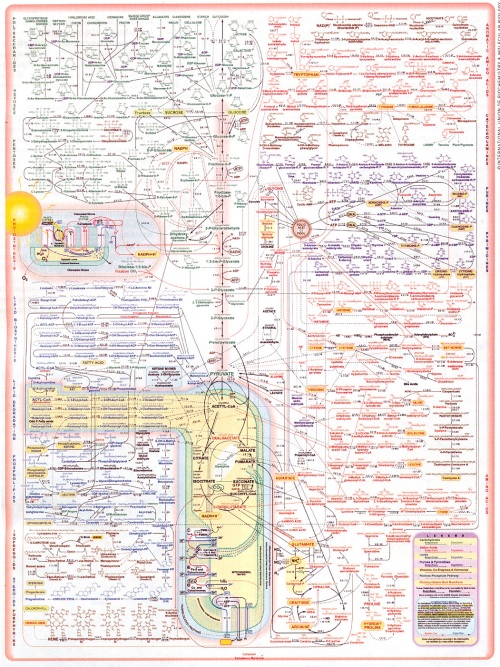

What Deleuze calls the “vital power that cannot be confined within species [or] environment” (quoted by Elena del Rio in her post at in media res) might profitably be thought in terms of “metabolism”—a process that is neither in my subjective control nor even confined to my body (as object) but which articulates organism and environment together from the perspective of a pre-individuated agency. Metabolism is affect without feeling or emotion—affect as the transformative power of “passion” that, as Brian Massumi reminds us, Spinoza identifies as that unknown power of embodiment that is neither wholly active nor wholly passive. Metabolic processes are the zero degree of transformative agency, at once intimately familiar and terrifyingly alien, conjoining inside/outside, me/not-me, life/death, old/novel, as the power of transitionality—marking not only biological processes but also global changes that encompass life and its environment. Mark Hansen usefully defines “medium” as “environment for life”; accordingly, metabolism is as much a process of media transformation as it is a process of bodily change. The shift from a cinematic to a post-cinematic environment is, as del Rio describes it, a metabolic process through and through: “Like an expired body that blends with the dirt to form new molecules and living organisms, the body of cinema continues to blend with other image/sound technologies in processes of composition/decomposition that breed images with new speeds and new distributions of intensities.” To the extent that metabolism is, as I claimed, inherently affective (“passionate,” in a Spinozan vein), del Rio is right that post-cinematic affect has to be thought apart from feeling, certainly apart from subjective emotion. Del Rio’s alternative approach, which (in accordance with Deleuze’s mode of questioning while thinking beyond the time-image) asks about the image, taking it as the starting point of inquiry, is helpful. The challenge, though, becomes one of grasping the image itself not as an objective entity or process but as a metabolic agency, one which is caught up in and defines the larger process of transformation that (dis)articulates subjects and objects, spectators and images, life and its environment in the transition to the post-cinematic. This metabolic image, I suggest, is the very image of change, and it speaks to a perspective that is the perspective of metabolism itself—an affect that is distributed across bodies and environments as the medium of transitionality. As del Rio rightly suggests, exhaustion—mental, physical, systemic—is not at odds with affect; rethinking affect as metabolism (or vice versa) might help explain why: exhaustion, from an ecological perspective, is itself an important, enabling moment in the processes of metabolic becoming.

Post-Cinematic Affect: Theme Week at In Media Res

This notice serves to advertise both a “medium” and its “message” (which, according to McLuhan is always another medium–and this is certainly true in this case). If you don’t already know the website In Media Res (the “medium” in question), you should definitely take a look. It’s an innovative and exciting project that works like this: each week, a group of people deal with a given media-related topic or theme (the “message,” so to speak) through the mixed media of a short video clip (30 sec. to 3 minutes in most cases) and a short textual accompaniment (between 300 and 350 words)–the medium’s message, itself media-oriented, is very literally composed of other media.

Now, the message has arrived that next week, the topic of discussion will be Steven Shaviro’s Post-Cinematic Affect, about which I recently posted. I quote here from Adrian Ivakhiv’s blog immanence:

Next week, the Media Commons project In Media Res will be hosting a theme week on Steven Shaviro’s Post-Cinematic Affect (which I wrote about here).

I’ll be guest curating the discussion on Wednesday, and Steven will be responding on Friday.

Here’s the full line up:

- Monday August 29: Elena Del Rio (University of Alberta, Canada)

- Tuesday August 30: Paul Bowman (Cardiff University, UK)

- Wednesday August 31: Adrian Ivakhiv (University of Vermont, USA)

- Thursday September 1: Patricia MacCormack (Anglia Ruskin University, UK)

- Friday September 2: Steven Shaviro (Wayne State University, USA)

To participate you will need to take a moment to register here.

This promises to be an exciting event, and it should be especially interesting to members of the Film & TV Reading Group. Mark your calendars!

Steven Shaviro on “the post-cinematic”

Steven Shaviro, probably best known for his now-classic book The Cinematic Body (an early but still one of the best explorations of the meaning of Deleuzo-Guattarian theory for embodied spectatorship; and one that Shaviro himself has critically reconsidered from a distance of 15 years in an essay called “The Cinematic Body Redux”), has recently published a book entitled Post-Cinematic Affect (Zero Books, 2010), which is summarized, on the publisher’s website, like this:

Post-Cinematic Affect is about what it feels like to live in the affluent West in the early 21st century. Specifically, it explores the structure of feeling that is emerging today in tandem with new digital technologies, together with economic globalization and the financialization of more and more human activities. The 20th century was the age of film and television; these dominant media shaped and reflected our cultural sensibilities. In the 21st century, new digital media help to shape and reflect new forms of sensibility. Movies (moving image and sound works) continue to be made, but they have adopted new formal strategies, they are viewed under massively changed conditions, and they address their spectators in different ways than was the case in the 20th century. The book traces these changes, focusing on four recent moving-image works: Nick Hooker’s music video for Grace Jones’ song Corporate Cannibal; Olivier Assayas’ movie Boarding Gate, starring Asia Argento; Richard Kelly’s movie Southland Tales, featuring Justin Timberlake, Dwayne Johnson, and other pop culture celebrities; and Mark Neveldine and Brian Taylor’s Gamer.

Now, over at his wonderfully named and always intriguing blog The Pinocchio Theory (which you can also always find in the handy “blogroll” on the right-hand side of this very blog), Shaviro has begun outlining the meaning of “the post-cinematic” as it appears in that book. This is what Shaviro says about the purpose of his theorization of “the post-cinematic”:

The particular question that I am trying to answer, within this much broader field, is the following: What happens to cinema when it is no longer a cultural dominant, when its core technologies of production and reception have become obsolete, or have been subsumed within radically different forces and powers? What is the role of cinema, if we have now gone beyond what Jonathan Beller calls “the cinematic mode of production”? What is the ontology of the digital, or post-cinematic, audiovisual image, and how does it relate to Bazin’s ontology of the photographic image? How do particular movies, or audiovisual works, reinvent themselves, or discover new powers of expression, precisely in a time that is no longer cinematic or cinemacentric? As Marshall McLuhan long ago pointed out, when the media environment changes, so that we experience a different “ratio of the senses” than we did before, older media forms don’t necessarily disappear; instead, they are repurposed. We still make and watch movies, just as we still broadcast on and listen to the radio, and still write and read novels; but we produce, broadcast, and write, just as we watch, listen, and read, in different ways than we did before.

The full thought-provoking post, which is highly recommended, can be found here. Enjoy!